Privacy commissioner hasn’t approved new gov’t contact tracing app

News | 06/18/2020 3:48 pm EDT

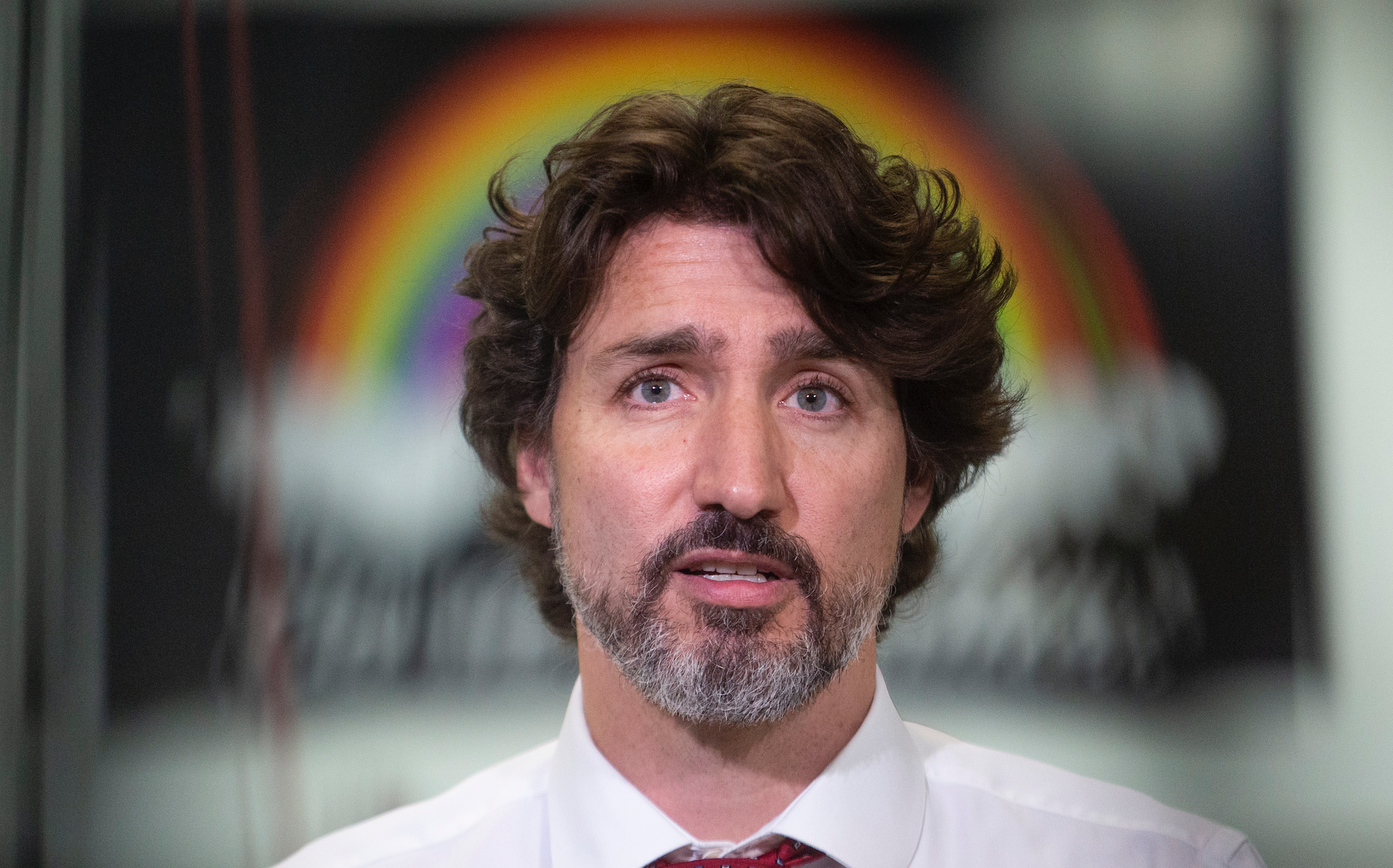

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Thursday that in developing the federal government’s new voluntary app to trace exposure to the COVID-19 virus, it consulted the Office of The Privacy Commissioner, but a statement from the OPC indicated the office has not approved the app Trudeau announced Thursday.

“The privacy commissioner has been worked with on this app,” Trudeau said during Thursday’s press conference.

But in an emailed statement Thursday, an OPC spokesperson said the privacy commissioner’s office hadn’t yet given its response about the proposed app to the government.

“We were recently contacted by Health Canada about a COVID-19 exposure notification application. We have requested and are awaiting necessary information and, until such time as we receive that information, we have not provided our recommendations to the government. We are working diligently and responsibly to develop that advice,” the statement said.

The app will use Bluetooth information about phones’ proximity to each other to track contact.

“If you test positive for COVID-19, a health care professional will help you upload your status anonymously to a national network. Other users who have the app and have been in proximity to you will then be alerted that they’ve been exposed to someone who’s tested positive,” Trudeau said.

“At no time will personal information be collected or shared and no location services will be used.”

The government is working with Shopify AB and BlackBerry Ltd. to launch the app, which will use the API launched by Apple Inc. and Alphabet Inc.‘s Google. That software doesn’t track the geographic location of phones, but it does track how close one device gets to another phone, which allows users to be notified if they were in contact with someone who later tests positive, or notify others.

“There will be a database of randomized codes associated with each smartphone that has this app that will be divided into two columns, those who may have tested positive and those who have not tested positive,” Trudeau said.

“So if your phone gets in proximity for a certain amount of time and a certain closeness to another phone, it will register it has had contact with that anonymized… identifier for the app.”

Trudeau said the app, which will be customised for each province and launch in July, will be simple to use and sit in the background of a phone once downloaded.

“Because it’s completely anonymous, because it’s low maintenance, because it is completely respectful of your privacy, also including no location services or geo-tagging of any sort, people can be confident that this is an easy measure that they can have to continue to keep us all safe,” he said.

Trudeau said Ontario would soon begin testing the app. “There are already a number of other provinces, including B.C., who are working with us on this, but it will be available to everyone in the coming weeks,” he added.

When asked whether there’s a specific percentage of the population the government is hoping will download the app, Trudeau responded that “any level of uptake would be useful” but that if usage reached 50 per cent or more, “then it becomes extraordinarily useful… it’ll actually allow us to have a better sense of when there are spikes or resurgences of a virus in a particular area or not.”

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, provincial and federal governments have indicated their interest in using location data to track the spread of the virus, but so far only Alberta has launched an app. Experts told The Wire Report in March there are no legal restrictions on using de-identified location data for contact tracing.

In a press release, advocacy group OpenMedia said the new app could be a “positive first step for privacy.”

In April, OpenMedia together with the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, the B.C. Freedom of Information and Privacy Association, the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group, and the Samuelson-Glushko Canadian Internet Policy & Public Interest Clinic at the University of Ottawa (CIPPIC) released a statement of principles for contact tracing.

“Unlike options the government has rejected, the proposed COVID Shield solution appears to meet most of these principles,” the press release said. Those principles include being opt-in, anonymized “peer to peer, with minimal extension of government surveillance powers and clear limits on how any data can be retained and used.”

Speaking at the Privacy and COVID-19 Mini-Summit hosted by the Canadian Anonymization Network Wednesday, Alberta’s privacy commissioner Jill Clayton said the Alberta app is one of the “least intrusive” versions of contact tracing apps available.

Similarly to the federal app, the Alberta app maintains an “encounter log” using Bluetooth proximity data, and does not track users’ geographical location. If users test positive for COVID-19, they can voluntarily share that encounter log with Alberta Health, Clayton said.

“It’s a decentralized storage of de-indentified Bluetooth contact logs on your phone. It doesn’t go to anybody in Alberta Health or government until you decide to do that,” she said.

Despite that, Clayton said she does have concerns.

“I have lots of questions. We have provided lots of questions,” she said. Clayton said that her office’s review of the ABTraceTogether app, launched in May, is almost complete.

“I will say my top concerns have to do with secondary uses. I want to know that the information is not going to be used for things like quarantine enforcement, or that employers aren’t going to get this information, and on and on and on.”

Speaking on an earlier panel, University of Ottawa law professor Teresa Scassa said that the roll out of contact tracing apps may be hampered by worries about data usage.

“We seem to be more concerned about sharing this information with government than we are about sharing it with the private sector, which is interesting. Maybe we should be more concerned about sharing it with the private sector,” Scassa said. She explained that there are concerns about the use of data for commercial purposes and what she called “function creep” where the use of data shifts over the course of time into areas not related to public health.

Scassa also called for the release of privacy impact assessments as well as information about what kind of rate of uptake would be needed for contact tracing apps to be effective.

“Alberta has not publicly declared what it considers to be the necessary uptake of its app for success; transparency about the ongoing of after-the-fact assessment of the utility of any apps that are adopted,” she said.

Echoing the comments made by federal privacy commissioner Daniel Therrien in May, Scassa said a lack of trust may hamper the apps usefulness.

“Where are the trust deficits? Is it government? Is it law enforcement? Is the concern: do we trust public health authorities to do this but we’re worried about law enforcement access or broader government having access?”

“There are a lot of issues that relate to both privacy and trust that need to be addressed with respect to these apps because of the potential implications that they can have for people,” she said.

— With reporting and editing by Anja Karadeglija at akarad@thewirereport.ca and Michael Lee-Murphy at mleemurphy@thewirereport.ca