Broadband blues: the UBF and its discontents

News | September 3, 2021

With a federal election called for Sept. 20, parties have pledged to make Canadians’ lives better in a myriad of ways, including by connecting rural and remote communities to quality internet. The government has had a vision for increased connectivity for years, even before the COVID-19 pandemic amplified the need as people were forced to work, learn, and entertain themselves from home.

The Liberal Government has been working to connect communities through funds like its $2.75 billion Universal Broadband Fund (UBF), with a target of making it possible for all households in Canada to connect to high-speed internet service by 2030 — 98 per cent of which are expected to be able to connect by 2026. However, advocates and community leaders have been questioning for a while whether or not the target speed of 50/10 Mbps for universal access is reasonable and if the nearly $3 billion the government pledged to spend on connectivity is even enough to encourage and fund infrastructure builds.

In its platform released Wednesday, the Liberal party promised to pressure national carriers that have purchased the rights to build broadband to accelerate wireless and high-speed internet connectivity work in rural and northern Canada.

The party says its “use it or lose it approach” would help it meet unspecified broadband access milestones between now and 2025. If its milestones aren’t met, the party says it would mandate the resale of spectrum rights and reallocate that capacity to smaller, regional providers.

It’s a means of connecting communities that could prove to be successful, as demonstrated by areas throughout the country where people have already taken matters into their own hands because they feel left behind by the government and major carriers such as BCE Inc., Rogers Communications Inc., Telus Corp., as well as some of the smaller providers. However, they say funds need to be accessible for still-smaller community groups to be able to do it.

Community-led connectivity

In Swan Lake First Nation in Manitoba, Gerald Thunderbird-Sky has taken on a new role setting up a local internet service provider (ISP) for the community — practically duplicating the work he did over about ten years in his home community of Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, also in Manitoba.

Thunderbird-Sky was first driven to help set up an independent ISP in Sioux Valley Dakota Nation after returning home from away and making inquiries about internet providers, through which he found few options with the quality of service he needed.

This led to DakotaNET, which Thunderbird-Sky built up from a few dozen or so residential customers and a handful of businesses to a local ISP serving the community and surrounding areas with almost 500 household customers, 20 businesses, several of its own tower sites, and an expansion into home security services.

“A lot of the challenge was more in gaining access to capital to do the upgrades because, especially in First Nations communities, you have it all on the table,” Thunderbird-Sky said in an interview with The Wire Report. “You have all these proposals, and one is ‘do we need fresh drinking water,’ or ‘do we need to fix this road, do we need this school bus fixed, or do we need internet?’”

Now, DakotaNET is looking into eventually offering gigabit speeds to its customers. At the end of June, it announced it is installing fibre optic cable to homes throughout the community, with the expectation that construction would be done around Sept. 10.

“In 10 short years, we went from 512kbps download and 256kbps upload speed to 100mbps+ symmetrical speeds and beyond,” DakotaNET said in a release.

However, there were some headaches and hurdles along the way in establishing itself as a legitimate ISP, including gathering support as it got going, “getting to the point where we had enough put into it where it was sufficient to offer as a service and get people to migrate from other providers that weren’t necessarily providing what you’re paying for,” Thunderbird-Sky said.

“When you’re dealing with a shoe-string budget it’s pretty difficult to justify the need. I had to get really creative in expanding and growing and I think that was the slowest part, the first five years,” he said.

Thunderbird-Sky is far from the only person working to connect a community where they may feel they have been left behind or altogether ignored by ISPs and government initiatives. While companies such as Telesat Corporation promise connections in rural Canada and in the far north while getting to the forefront of the so-called new space economy — with more than $1 billion in support from the federal government, in Telesat’s case — should the priority be on racing to the top, or on connecting smaller communities to adequate broadband services in the first place?

Broadband throughout Canada

Available broadband speeds do appear on paper to have been increasing across the country, though advocates say there is work to be done on supporting projects to keep that growth going, even in areas pictured to have hit the 50/10 Mbps goal.

Josh Tabish, public affairs manager with the Canadian Internet Registration Authority, said in an interview that the not-for-profit .CA domain manager has heard of “frustration” with the Universal Broadband Funding program from a number of communities.

“The government basically says if you have access to 50/10 speeds or better in your community, you don’t get funding, you don’t qualify,” he said.

“The problem that we’re hearing from folks is that the government is basing that eligibility on their broadband map, which is based on data supplied by the ISPs.”

Rural broadband availability at 50/10 Mbps speeds grew from 40.8 per cent of rural households in 2018 to 45.6 per cent of rural households in 2019, while urban households with access to 50/10 speeds climbed from 85.7 per cent in 2018 to 87.4 per cent in 2019, according to the CRTC’s Communications Monitoring Report for 2019.

The proportion of internet subscriptions that had 50/10 Mbps or faster increased from 49.5 per cent in 2018 to 58 per cent in 2019, and residential high-speed internet subscribers downloaded an average of 245 GB a month, a substantial increase of 26.9 per cent from 2018.

“Of course the speeds that are actually received by end-users are often slower than what the advertised speeds,” Tabish said.

In 2019, the communications sector brought in some $71 billion in revenue, $54.1 billion of which was made through telecommunications, which saw “ever-increasing amounts of data through both fixed internet and mobile services.” The five largest providers — Bell, Rogers, Shaw Communications Inc., Telus, and Quebecor Inc., accounted for 87.3 per cent of all telecom revenue, the report stated.

As for those companies, Thunderbird-Sky believes there is a lack of incentive for them to invest independently.

“We don’t have the density to justify their investment and that’s the key to all of these problems we’re having with rural growth and internet. There’s no incentive for them — you’d think federal funding would be incentive enough because it’s not coming out of their pockets,” Thunderbird-Sky said.

“It needs to stop being about that bottom line and it needs to start being about providing the service.”

Government funding

Ideally, this is where government funding such as the $2.75 billion Universal Broadband Fund — which was announced as a $1.75 billion fund in fall 2020 and later topped up through the 2021 federal budget — could bridge the gap to assist investment in rural, remote, and Indigenous communities.

Money began flowing through the UBF with the rapid response stream, which made up to $150 million available for projects that could be completed by Nov. 15, 2021. There is also the CRTC’s $750 million rural broadband fund which began announcing recipients last summer, a $600 million agreement for low earth orbit satellites (LEOS) with Telesat, a $2 billion Canada Infrastructure Bank fund for larger projects, the oft-criticized Connect-to-Innovate program, and a number of provincial-level initiatives.

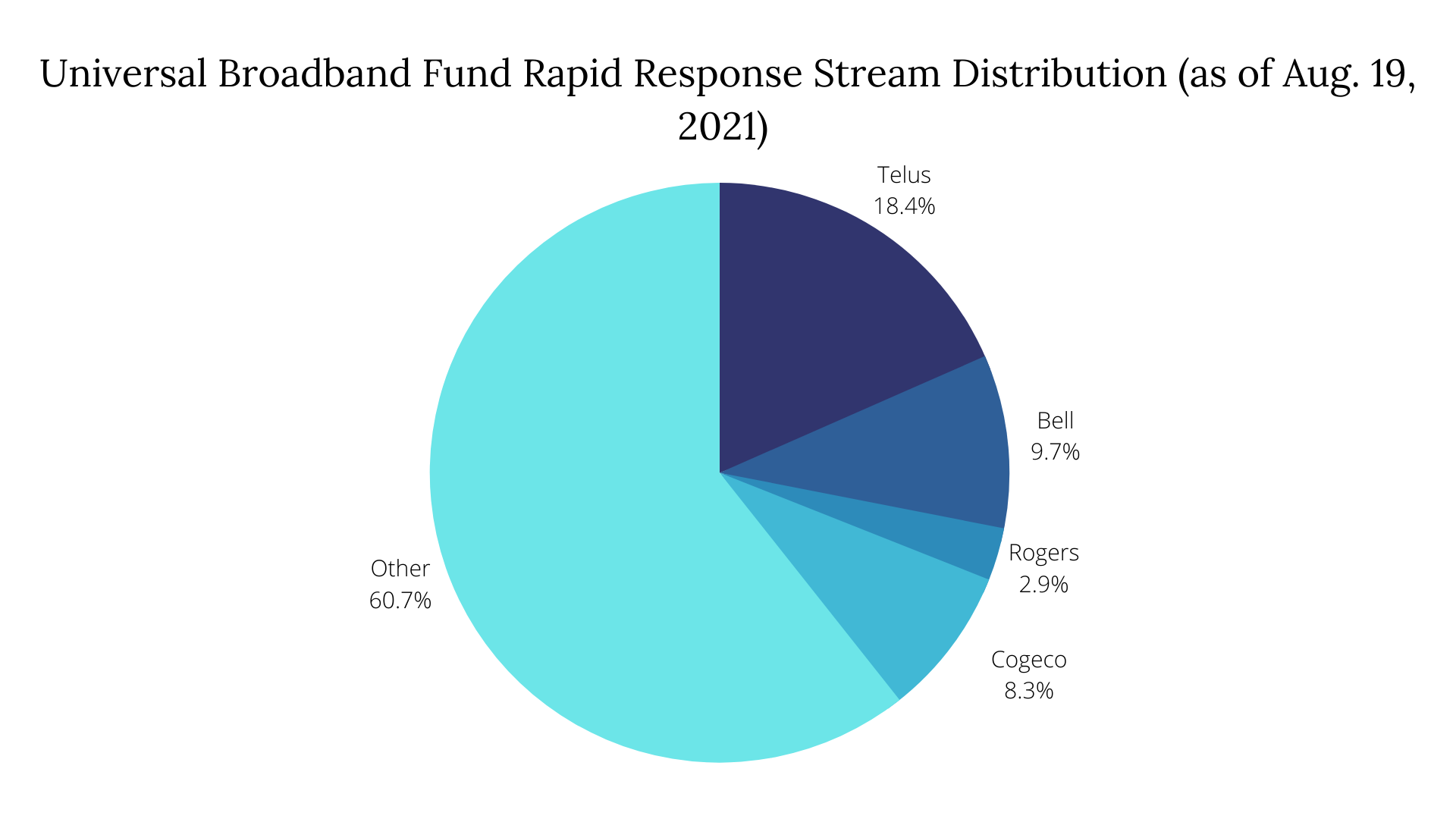

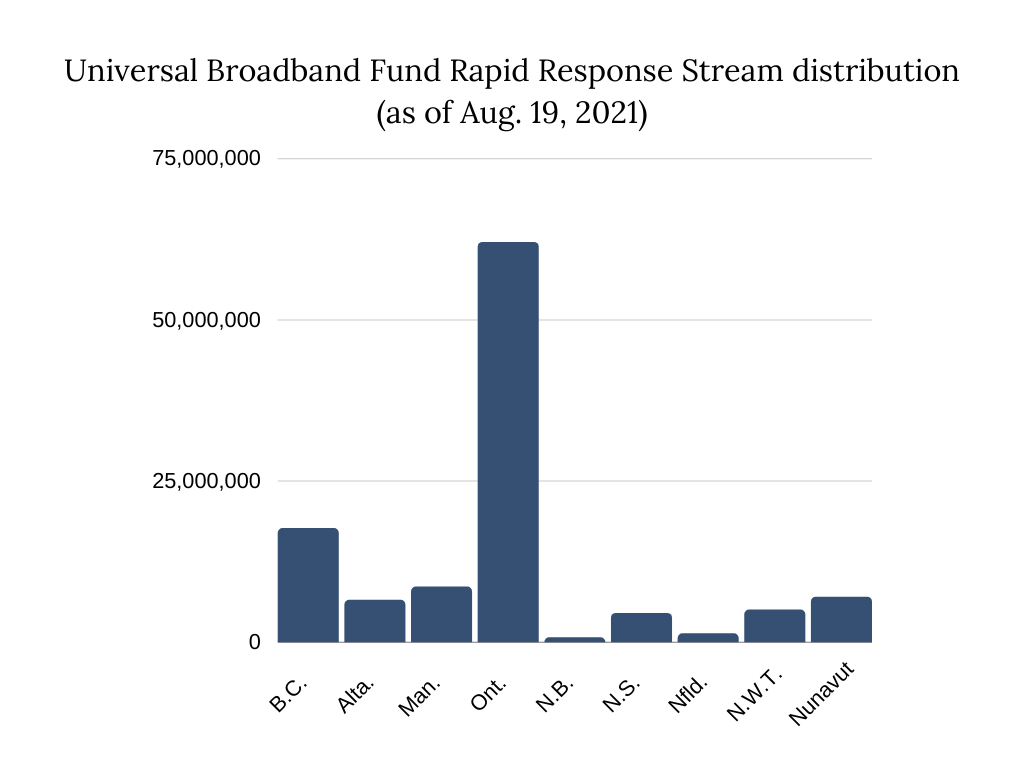

So far, more than $110 million has been given out to projects all over Canada through the UBF’s rapid response stream covering a total of about 70,000 households in a variety of communities. A spokesperson for Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) said in an email that as of Aug. 19, some 130 different projects have been announced. A majority of the money has so far landed in Ontario, with more than $60 million going to projects in the province.

Most of the money — more than $60 million — has gone to smaller ISPs, perhaps demonstrating that the government does have an eye on the power of community groups to effectively connect their residents in areas more profit-seeking companies may not want to touch. There’s plenty more yet to be disbursed with the target of making 50/10 Mbps available for all Canadians in mind.

Is 50/10 Mbps a reasonable goal for 2030?

The 50/10 Mbps target itself was set in 2016. At that time, the CRTC estimated two million Canadian homes — or 18 per cent — did not have access to those speeds. Beyond the issue of funding, a more pressing question to some is how long 50/10 Mbps will be the recommended standard for service — or even if it should be the minimum standard now.

In 2014, when the government was working to enhance broadband service to target speeds of 5 Mbps through funding initiatives, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) put out a report titled “Broadband Access in Rural Canada: The role of connectivity in building vibrant communities,” in which it considered how outdated the minimum goal of the day already was.

“While a universal speed of 5 Mbps has been proposed by the CRTC, and is the current focus of the federal government, there are reasons to believe this may not be adequate now, let alone in the near future,” the report said just seven years ago.

Citing another report by Nordicity presented to the three northern territories, the FCM report stated “for example, speeds of 9 Mbps were suggested for residential use, 11 Mbps for educational use, and 16 Mbps for healthcare applications. All of these speeds were identified as being required today.”

“Caution needs to be exercised with respect to determining what minimum speeds should be delivered to communities,” the report said.

Thunderbird-Sky, one of many who has been part of an application to the Universal Broadband Fund, has also questioned the longevity of the government’s 50/10 Mbps goal.

“I get that they had to say something, there needs to be some kind of standard set, but the reality is they set the bar so low but they’re also not allowing themselves to get creative with the solution,” he said.

“I think this problem is just going to extend past 2030. I think we’re going to get to the point in 2028 where it’s ‘you know what, we’re not even close, the infrastructure just isn’t there, we’re having trouble reaching the north. Whatever excuse it is, we’re going to extend it to 2045.’ By then, even a 100/100 by then is going to be considered too slow,” Thunderbird-Sky said.

“We’re in a time where the ‘internet of things’ is becoming a part of everyone’s lives, especially the cities. You’ve got Nest cameras, Ring doorbells, fridges monitoring your food, cameras in fridges now, smart homes. That all requires massive amounts of data.”

The FCM report also said, “it is important to note that some of the solutions that are being employed are not sustainable in the long run… rural customers, by virtue of their small numbers and the technical challenges in delivering these same advancements, make the investment case for any operator very difficult without government support.”

Whose best interests are in mind?

Now the executive director with Teach for Canada, a group recruiting certified teachers to northern First Nation communities, Ken Sanderson spent four and a half years with Broadband Communications North (BCN), an Indigenous-owned nonprofit telecommunications company in Manitoba that’s been operating for close to 20 years. He too is wary of promised speeds versus reality in the communities he is trying to send teachers to as he continues to follow developments in the broadband space.

Sanderson said in an interview that BCN, which bills itself as the largest Indigenous network in Manitoba, was set up because a lot of First Nations communities, especially those further north or away from urban centres, aren’t getting the attention they deserve.

“Let’s face it: in a lot of these communities, you won’t make a profit serving them. You’re lucky if you don’t lose your shirt servicing them, which is why BCN was set up as a nonprofit,” he said, adding that communities were tired of waiting for service with millions of dollars going into private hands — a sentiment which has not waned.

“You have these multi-million-dollar telcos getting crazy amounts of money and there’s not much they’re doing with it. They’re getting the funding but they’re still passing the cost off to the residential people,” he said.

Before DakotaNET found its current uplink provider, Thunderbird-Sky said one particular provider approached them saying they would work on a fibre connection from Brandon, Manitoba, to Sioux Valley Dakota Nation for an investment from the community of about $1.2 million.

He said a community between Brandon and Sioux Valley, called Alexander, was not yet part of the provider’s network but would have benefitted from the project as well. He felt the company may have been trying to piggyback off his own community’s investment and make a profit off of it instead of putting down its own money.

Funding Sustainability

Another question raised by those discussing broadband connectivity is whether or not the Universal Broadband Fund contains enough money for the work needed to connect every home in Canada — though advocates agree it’s still good to see money flowing. Broadly speaking, it seems people with experience in the industry expect billions more would be necessary, though there isn’t one perfect number.

Friday, the Annapolis Valley, N.S.-based i-Valley Intelligent Community Association, a not-for-profit working with communities in Atlantic Canada and elsewhere on arranging high-speed networks, put out a release calling on federal parties to “take a new approach to broadband creation,” proposing a number much higher than the few billion available now.

“Broadband is Canada’s number one priority; almost all progress in the past sixty years has come because of networked innovation,” i-Valley president and co-founder Terry Dalton said in a release. “Canada has made progress, but we are still woefully short of the resources we need to arm our people with access to modern health care, emergency services, and economic and social growth.”

i-Valley suggests closing the broadband gap would require some $50 billion, which is in the same range suggested by other sources familiar with the industry. The group wants parties to endorse a “unified development strategy” that is not based on communities competing for funding, an economic cooperation structure that brings together community, private, provincial, and federal funding, and an accessible fee structure for broadband use based on community governance of the network, “as Canada’s private companies have created the world’s most expensive network access fees.”

South of the border, the United States government is working toward spending $65 billion on high-speed broadband connections for every household, the majority of which is to fund network deployments. Though the United States has a population roughly eight times the size of Canada, there is still plenty of terrain to cover at home. Originally, U.S. President Joe Biden proposed a $100 billion spending plan for broadband, with some money reportedly prioritized for government-run and non-profit networks.

In Canada, Thunderbird-Sky noted that infrastructure costs will likely vary widely based on terrain.

He said in his area, where there are flat plains and few forests, infrastructure costs per kilometre might come in at about $14,000. However, he anticipates in some of the more northern areas of Canada with massive boulders and perhaps swampy or otherwise rough terrain — and where contractors may have to get below the frost line — $14,000 could easily turn to $40,000 or more.

The sole project awarded money in the Northwest Territories through the UBF will receive up to $5 million to connect 152 households in the community of Whatì, plus $3 million from the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency, $1.5 million from the Tłı̨chǫ government, and $1.4 million from the government of the Northwest Territories.

Meanwhile, in North Spirt Lake, Ont., First-Nations owned and operated K-Net is set to receive up to $309,888 to connect just six homes in the community.

Public Interest Advocacy Centre executive director and general counsel John Lawford said projects in rural and remote Canadian communities could also be more likely to be abandoned or shoddily patched up by certain providers down the road as infrastructure ages and becomes more expensive to maintain in communities where it may make little economic sense to pour thousands of dollars into maintaining good service.

Sanderson agreed, suggesting local non-profit structures would be more fit to lead in many communities.

“There’s no business case for a lot of these communities, and these application processes need to stop pretending that there is,” with decision-makers putting in calls to local leaders instead, he said.

“That’s what all of this dovetails back into. We’ve created a system of funding that is incentivizing low-quality builds.”

Future-proofing broadband

In parts of Atlantic Canada, the housing market has experienced a boom in sales during the pandemic, topping industry records as out-of-towners look to leave more urban markets such as Toronto and the surrounding areas. Many are taking advantage of employers moving to remote work, selling their homes in the city to buy in more rural areas and move on to a different quality of life.

However, the first question many of those movers ask is how good the local internet is, according to i-Valley’s Dalton.

Region” from the World Council on City Data. (Contributed)

Dalton, who has spent years working on connecting communities in Nova Scotia and was with the National Research Council of Canada for 25 years, told The Wire Report in an interview that COVID-driven adoption of telehealth, online learning, remote work, and the like “are putting pressure on improving broadband capability.”

“This is a trend we have to jump on right now, but we can’t. The networking isn’t there,” Barry Gander, Dalton’s i-Valley co-founder, said of the potential to attract remote workers to rural areas.

In order to improve networks, Gander and Dalton have a similar view to others working on rural connectivity. They want to see fibre equipment installed during the development phase of roads and buildings to minimize costs later on and maintain an emphasis on fibre, which seems to be widely regarded as more future-proof than wireless infrastructure.

“Until you get anchor fibre into the communities you can’t take it any further because fibre is the holy grail when it comes to increasing capacity, demand, quickly — not wireless,” Dalton said.

“Wireless technology, you’re going to have to change out every three, five, seven years regardless. Whereas fibre can be changed quite quickly and affordably compared to wireless where we’ve got to do a forklift, rip-and-tear replacement,” he said.

i-Valley is working on a project to connect homes in Pictou County, N.S., for $72 million — including some government funding. It’s a majority-fibre build, the duo said, but with some wireless infrastructure being used to keep them within their budget, otherwise, they would be pushing $100 million to get fibre into every home.

The network, which received several million in funding from the municipality as well, will have a revenue-sharing model and open access pricing and choice, according to an Aug. 2020 release.

“The Municipality of Pictou County and i-VALLEY chose a consortium of providers led by Nova Communications, a division of ROCK Networks to perform engineering planning and network construction, with NCS Networks being the lead Internet service provider,” it said.

Dalton and Gander are working on educating people about the potential an open-access fibre network would have in certain communities to connect all homes and businesses.

“It can be done, and it can be done successfully. It takes time… but it takes an open-access network — one that is not owned by a private company. Build it once and have multiple service providers use the infrastructure to deliver what they do best,” Dalton said.

“We’re past the point where a company can safely install networks for everybody,” Gander said.

“Frankly, the Bell Canada’s of this world, while they’re great companies, they don’t know how to provide networks to rural areas. They don’t do that,” Gander said.

Dalton and Gander are not the only ones considering the future of fibre and how we should be preparing for it.

“The best practices that we hear from our counterparts around the world when it comes to building out networks is that that kind of shared-conduit infrastructure can really lessen barriers to the deployment of next-gen networks. If conduit is being laid as a part of all major infrastructure and road construction projects, that really reduces the cost to put down fibre” CIRA’s Tabish said.

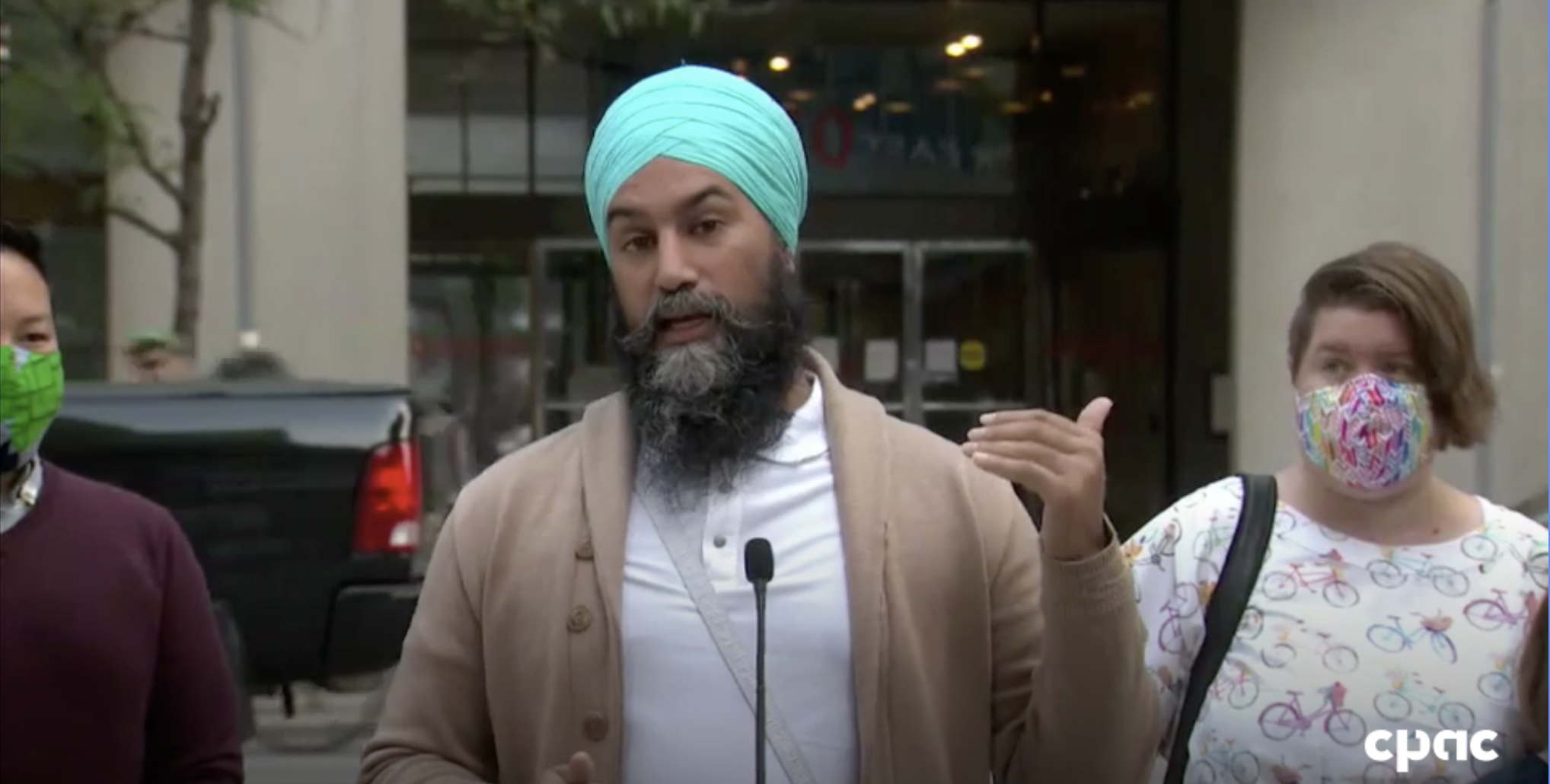

During a stop in New Brunswick to kick off his pre-election tour of Atlantic Canada, NDP leader Jagmeet Singh responded to a question from The Wire Report on whether or not he has considered the issue of rural connectivity by suggesting the NDP might take on this approach.

He said the party would consider investing in broadband “the way we would invest in roads and bridges. We look at it as public infrastructure. We need to look at our access to the internet in the same way. It is essential, people need it, it would help revitalize a lot of rural communities and help them catch up with urban communities. So that’s something really important for me.”

Project Oversight

In addition to all of this, some are questioning whether there is enough oversight on how government money is spent once received by companies including Bell, Telus and Rogers, and other more regional providers.

PIAC’s Lawford told The Wire Report the government is not being strict enough to ensure companies that receive broadband fund money are actually providing 50/10 Mbps as required, even if they advertise that as an available speed tier.

“Everybody always uses vague words like high-speed internet or broadband without telling you what speeds, or they say they’re going to give up to 50/10. Well, that’s not the right speed. They’re cheating, and they can get away with it,” he said.

For its part, Tabish said CIRA is “really pleased to see all the money that’s been put up to connect folks, but we are concerned about how the success of this program is being measured.”

“How do we ensure that internet users actually get the internet speeds they’re promised? We’ve got all this money put up, projects are starting to get funded, but I think there’s an opportunity here to really maximize the impact of that funding through independent performance audits of the projects that receive public funding.”

Tabish said there aren’t really any testing requirements for the broadband fund to ensure projects actually deliver on their promises or meet the CRTC’s minimum service thresholds.

“This is a problem because we know that internet service operates on a best-effort basis; real-world speeds don’t always live up to advertised speeds, but what it really means is that if you don’t test these projects, residents in currently underserved areas may not end up getting 50/10 in the end, and that will be a real shame,” he said.

“Our recommendation is for the government to institute an independent, third-party assessment of all these publicly-funded projects to make sure they meet the CRTC’s universal service objects and I think that would help taxpayers make sure they get the maximum return on their investment.”

In order to perhaps deal with some of these concerns, Lawford suggests a “broadband Czar” to administer all federal broadband funding — reiterating an argument made by PIAC to the House of Commons industry committee in December 2020 as it was discussing the affordability and accessibility of telecommunications services.

Lawford said in December that “everyone in this space — from the smallest cooperatives to the largest telcos, consumer groups, MPs — all complain about the fragmented government of Canada operation of these funds.”

When prompted during the hearing, Lawford said “It’s tempting to want to leave it with the CRTC, because they are the natural regulator in this area.”

“I don’t believe they have the statutory authority at the moment, perhaps this committee could consider that,” Lawford said, adding that the position of a Czar could be temporary to “get the whole house in order. Then we should perhaps think about legislation to formally give it to the CRTC.”

In January, representatives of Bell echoed Lawford’s suggestion of one responsible body in a way when they told the industry committee spectrum auction revenues should be reinvested in rural broadband initiatives and that the multiple broadband funding programs run by federal government programs should be combined into one. The recent spectrum auction brought in nearly $9 billion, with more than $7 billion of that credited to bids from the incumbents.

Combining the CRTC’s rural broadband fund and Innovation Science and Economic Development’s (ISED) Universal Broadband Fund, and potentially the Canadian Infrastructure Bank, should be considered to address Canada’s rural broadband needs faster and more effectively, Bell’s chief legal and regulatory officer Robert Malcolmson said at the time.

“The only thing I’ve seen that’s encouraged me in the last ten years is that slowly, telecom is becoming — because of broadband — finally an election issue. I have some hope that people can see through this complication and be generally upset that they’re paying a lot for telecom service,” Lawford said in a more recent interview.

“I don’t know where to start except for going back and rewriting the Telecom Act.”

If Canada were to rewrite its policies, Lawford suggests looking to other countries including the United States and the United Kingdom.

He said, for example, the 333-page United States Communications Act was modified more than 20 years ago to have clear universal service goals, saying everyone is entitled to advanced service.

“Of course, we have nothing that’s even close. We just have a policy objective about affordable and sustainable telecom across Canada.”

Who wins the race?

Depending on the results of the upcoming federal election, existing broadband connectivity initiatives could remain the same or be modified. As many people living in cities and better-serviced communities have grown accustomed to running their homes with smart technology and streaming videos with ease, will priority be placed on bringing the same convenience to rural and remote households?

As Thunderbird-Sky said, “you need high-speed internet to essentially run your home.”

“A lot of rural places, it’s just impossible. Even one or two surveillance cameras with cloud viewing, that’s going to tax your link to a point where it’s unusable. They need it too. They need the internet of things, they need to be able to have automation in their homes.”

Thunderbird-Sky points to agricultural businesses and farms, saying they could benefit from a number of new innovations from recent years — such as automated gates, machines, and feeding for cattle, for example — but they need the right broadband connection to do it.

“All of that could be done with remote view but the reality is there’s no infrastructure there. They’re making such a large deal about infrastructure but we know that it’s been done before. All these farms have copper phone lines,” he said.

He asserted that “would’ve been the time to run fibre, but they never expect copper to max out in speed.”

Moving forward, “they need to look back at the mistakes they made back then — limiting themselves on throughput and underestimating what the world needed,” Thunderbird-Sky said.

— Reporting by Hannah Daley at hdaley@thewirereport.ca and editing by Michael Lee-Murphy at mleemurphy@thewirereport.ca